Live Through This: One Woman’s Battle With Heroin

July 30th, 2013

One of the Many Graphic Images of Live Through This

Explicit images often serve as useful tool for exposing the devastating physical effects of drug abuse and addiction. Some of the most impactful drug-free campaigns have introduced revolting, despairing photographs in order to deter drug use and depict its incredibly harmful impacts. In the book Live Through This, Tony Fouhse puts the power of imagery to the test while capturing the raw, discomforting life of a heroin addict seeking recovery.

Fouhse- a photographer based in Ottawa, Canada- began the project in hopes of producing portraits of drug addicts in downtown Ottawa. He titled his series of photos User, referencing the addiction he documents. “You could see them (the addicts) change when I was photographing them- putting on a face that they wanted the outside world to see.”

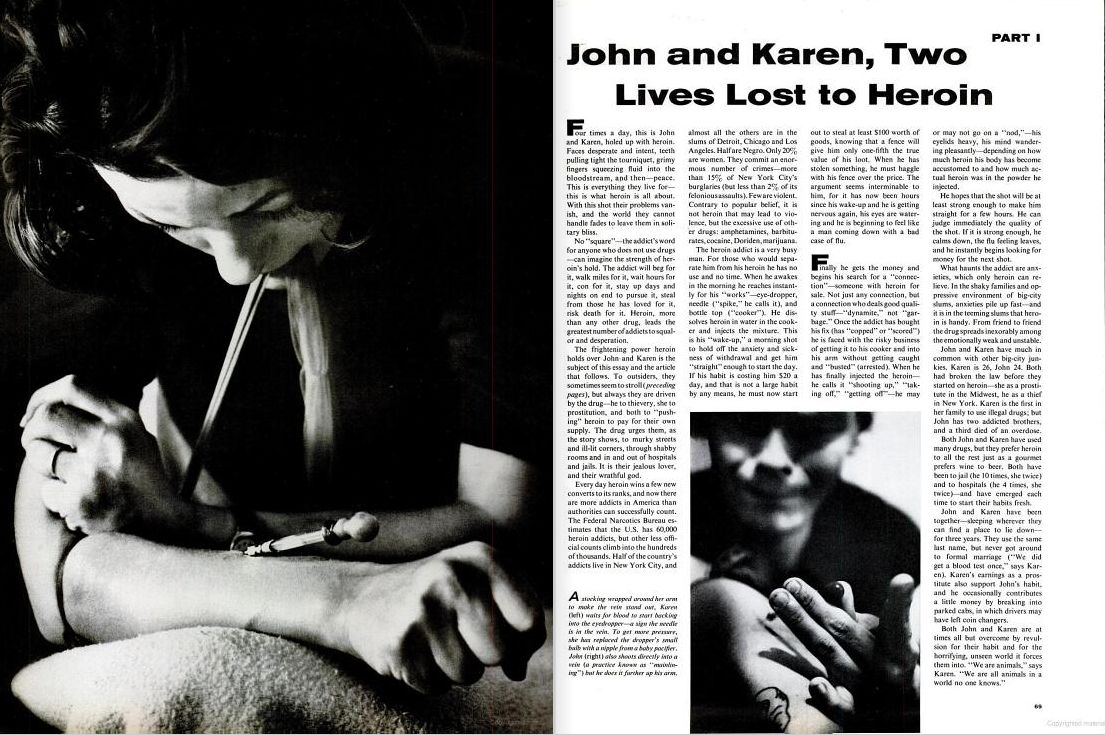

Past portrayals of junkies, like Bill Eppridge’s “John and Karen, Two Lives Lost to Heroin,” published in LIFE in 1965, and Larry Clark’s Tulsa in 1971, forged the path for photographers like Fouhse to immerse themselves in other people’s drug abuse and addiction.

Examples of Fouhse’s Photography in Life Magazine

However, unlike some past projects, Live Through This focuses on one person’s attempt to reclaim her life while embodying a story of addiction, suffering and hope of recovery.

The story begins with Fouhse candidly asking Stephanie MacDonald- the young heroin addict whose recovery he’s been documenting: “You know how this should have ended? You should have died.”

Fouhse first met Stephanie in June 2010, photographing her over a span of a few weeks until he bluntly asked her, ‘Is there something I can do to help you?” Stephanie, in turn, requested his help with getting into rehab, but one roadblock stood between Stephanie and treatment.

Before she could enter rehab, doctors discovered that Stephanie had a cerebral abscess- caused from injecting heroin- which would be fatal unless operated on. “After her (brain) surgery,” Fouhse notes, “she phoned me up and told me she wanted to go home. I asked her where her home was, and she said, ‘Your house.’”

Ultimately, Fouhse- along with his wife- welcomed Stephanie into his home in order for her to withdraw from heroin and begin rehab.

“The only two places she could have gone were to her dealers or the streets, where she would have died,” Fouhse explains. “So it was kind of out of our hands, in a way. We had to do this whether we wanted to or not.” Stephanie lived with the couple for almost a year and began helping Fouhse create the photographs used in the book.

The two collaborated on about 90 percent of the work sequencing the photos in chronological order, Fouhse comments. Each page illustrates the demeaning, vicious hold of addiction- the silent mental struggles and pains exposed outwardly on a person’s body for all to witness.

“We started this thing,” Fouhse writes, “Stephanie and I, as two people who just wanted something from each other. She wanted help getting clean and I wanted to take pictures of her. In the end, there was no distance.”

Stephanie included a short essay hidden in a pocket at the back of book, along with a recent photograph of her in her new home. She brings awareness to her struggles with getting clean and staying sober. Although she acknowledges that her future remains undecided, she allows herself to confront and contemplate her past battles.

Rita Baldini, Editor

AllTreatment.com

Sources: